Louie Kemp and Bobby Zimmerman met as kids at a Jewish summer camp in Wisconsin and became lifelong friends. Bobby went on to fame and fortune as Bob Dylan, becoming a music icon of his generation, and Louie as an entrepreneur who made it big producing imitation crab. Along the way Louie managed Dylan’s 1975 Rolling Thunder tour and shared a house with him in Los Angeles. In their late 30s, both men turned to religion, Dylan to Christianity and Kemp to Orthodox Judaism. In a conversation with Moment editor-in-chief Nadine Epstein about his new book, Dylan & Me: Fifty Years of Adventures (written with author and musician Kinky Friedman), Kemp recounts how he helped his friend deepen his understanding of Jewish texts and re-embrace Judaism.

How did you get to know Dylan?

Bobby was born in Duluth like me, same hospital as me. But then his family moved north to Hibbing, in the sticks. So, he grew up in a town 75 miles away. But we used to be together every summer at camp, and because my town was bigger and there was more action in my town, he’d come down and stay with me after camp.

What was your Jewish education like?

We went for five years to a Jewish camp, Herzl, and they kept kosher there, they kept Shabbos, an Orthodox rabbi ran the camp. But we didn’t have what you would call formal Jewish education. We were well prepared for our bar mitzvahs, but back in those days, the whole thing was to get up and read in Hebrew and make a good showing. They didn’t teach you the underlying meaning of what you were reading. In fact, I can still read Hebrew but I don’t know what the words mean. I think it was the same thing with Bobby. Few of the kids of my generation, unless they grew up Orthodox, which very few did, had a real Jewish education. We knew we were Jewish, we had Jewish pride, but we never studied Torah or Gemara or any of that stuff, so we really didn’t know the underlying meaning of Torah and Judaism.

Bob Dylan at camp, 1956

Yet you say Bob was always very Jewish. What do you mean?

Growing up in Hibbing, a blue-collar mining town, had an impact on Bob. The people there worked hard and often made a decent wage. But there weren’t a lot of possibilities for growth and advancement. Perhaps what had an even greater impact on his worldview was his Jewish upbringing. Every Jewish kid celebrating Passover knew the story of our people’s enslavement in Egypt. During Hanukkah we lit our menorahs in commemoration of our ancestors, the Maccabees, and their fight for religious freedom. We were taught about the Spanish Inquisition and the pogroms in Eastern Europe that accounted for many of our grandparents’ escape to America. As teenagers, we were struck by the reality of what had occurred not much more than a decade earlier in Europe, the Holocaust. In 1960 the movie Exodus, starring Paul Newman as a brave member of the Haganah attempting to lead a group of his people to freedom in Palestine, was released. I remember coming out of the Granada Theater on Superior Street in downtown Duluth furious, in a rage. I began pounding on a parking meter as my girlfriend, a Norwegian girl named Lee, tried to calm me down. “Louie,” she said, “it’s just a movie.” It was not just a movie to me. The injustices done to these poor survivors sickened me; it sickened many of us. Supporting the underdog is virtually second nature to Jews, as we have so often been in that position ourselves. We seem to have a sixth sense when it comes to persecution, discrimination and injustice, and many of us have devoted our lives to battling these things. There’s no question in my mind that Bob’s drive to write songs that mattered was born, at least in part, from his roots as a Jew.

In your mid-to-late 30s both of you turned to religion. Why?

We were looking for something more meaningful to fill in those empty feelings we had. He’d obviously been very successful on every level of Western society, and I’d been reasonably successful as well, but I know in my case I felt there must be more to life than just that. And I think he felt the same way.

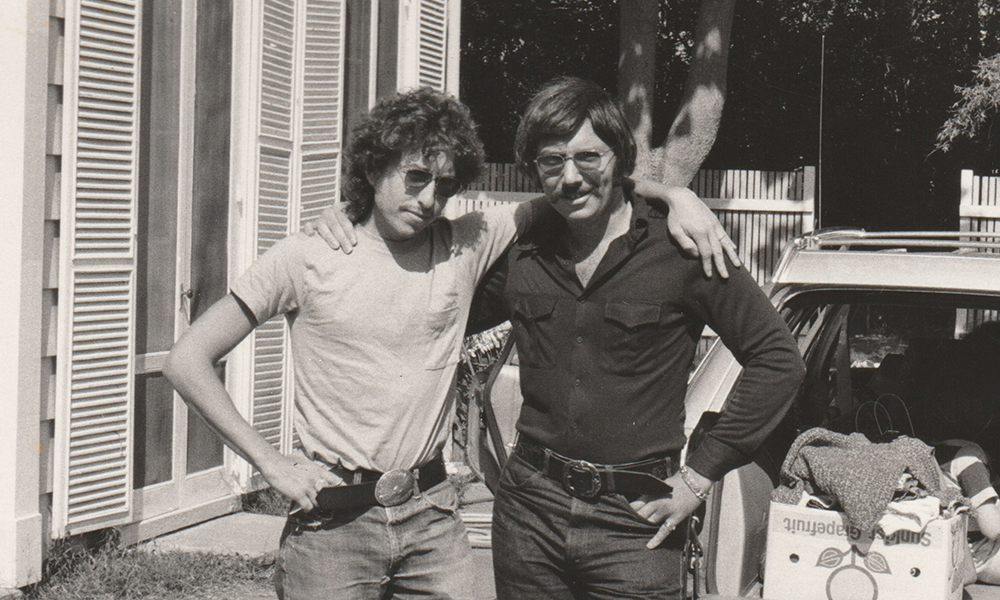

Bob as best man at Louie’s wedding, 1983.

What led you to become more Jewishly observant and Dylan to explore Christianity instead of Judaism?

I looked for deeper meaning within Judaism and I found it with Rabbi Manis Friedman, and was able to meet the needs of my spiritual yearning that way. Bob didn’t. He had a friend who took him to a New Testament Bible class. So that was his first introduction to learning Bible, but it happened to be the New Testament. If I had taken Bob to a Torah class before that, that never would have happened.

Not long after, the two of you ended up living together in a house in Los Angeles. How did that happen?

Bob was divorced at the time. His main house was in Malibu, but he used to come into town a lot, so he rented a house in L.A. because it was an hour drive. I was renting a condo in Westwood, and he used to come visit me there. So he says to me one day, “I rented this house and I got plenty of room. Come stay with me.” So I moved in in 1980. And for about three years we lived there together, until I got married in 1983.

What was it like living together, with both of you traveling in different religious directions?

It was a very interesting dynamic. He’d be in one room studying the New Testament, and I’d be in the other room studying the Torah. And then we’d meet in the kitchen and we would try to teach or persuade the other one about what we were reading and what we were learning. He was teaching me about what he was learning, and I was teaching him what I was learning, and there was contradictory information there.

Did you argue about Jesus?

Yes, Jesus would come up for sure. Through the process of study, he thought Jesus came to die for the sins of man, he was the son of God, and he was part of the Trinity, the Father, Son and the Holy Ghost. That is part of the New Testament. As I say in the book, I saw Jesus as a rabbi, teacher and another Jewish boy who’d made good. We had a lot of conversations about that, and obviously we weren’t on the same page there. He was being taught one thing and I was being taught another thing. And it was after a few of these conversations that I realized that he had been studying longer than me. He was more knowledgeable. I didn’t have counterarguments for a lot of his arguments. As a Jew, I just knew what I felt and knew, but I didn’t have historical reference points. Now I have some, of course. But then, I didn’t.

So what did you do?

I went in another room one day, after one of these discussions because I thought I was out-gunned, and I called Rabbi Friedman in Minnesota. I said, “Rabbi, I’ve got a friend who’s studying the New Testament and we have these deep discussions, and I’m not equipped to counter the points that he brings up. Could you do me a favor, if I bring you to L.A., will you meet with him?” I didn’t tell him who my friend was. He said, “Sure, if you want me to. I’ll be happy to.”

So he came out?

I flew him out the next week. But before I did that, I said, “Bob, my rabbi is going to be coming to L.A. next week.” Of course he wasn’t, but I was going to bring him. “Would you like to meet with him?” He said, “Yeah, sure, bring him over to the house.” I brought him out. And they got along good. Bob liked him. That was the beginning of the process. Later, I brought in other rabbis for him to study with and other observant Jews who were friends of mine and who were cool guys who I thought he’d relate to, and he did. Bob started to study Torah and Talmud and met with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the whole works. And that’s how I got him out. It took a while, but I got him out.

How long did it take?

I probably brought Rabbi Friedman out in February or March of 1981. It was a gradual process, but within two years it was done. It came in increments.

So he stopped being a Christian?

Well, he was always Jewish. In his mind I think he never thought he wasn’t Jewish, but in my mind he was like a Jewish person who appreciated Jesus. I still think he has some kind of historical appreciation for him, but he got deeply involved in studying Torah and Gemara and keeping Jewish customs and holidays.

Bob Dylan at his son’s bar mitzvah at the Western Wall, 1983.

Did he ever thank you? Or talk about it with you?

He didn’t have to thank me, our relationship wasn’t like that. Friends are just friends, and you do what you think is good for your friend.

This didn’t hurt your friendship? No, no, of course not. No, we got closer through it, I think. We were on the same page. We were always pretty much on the same page but when he took that deviation, I had to get him back and I did. Not only did I get him back to where he was before all this happened, he went much farther in Judaism through the process of studying.

Where are you today on the Jewish religious spectrum? And where is he today?

I can only speak for myself. I’m a Modern Orthodox observant Jew. I can’t tell you where Bob is. Traditionally, he’s always gone to High Holiday services, seders and all that. But I know he’s Jewish.

gee, and to think I never cared… (What a waste of an issue)