At the conclusion of Volume One of The Story of the Jews, Europe’s Jews were once more scattered to the ends of the known world, after the expulsion en masse from Spain in 1492 and Portugal in 1496. Four years later, Simon Schama returns with the second volume, which takes his epic chronicle of Jewish history through to the start of the Dreyfus Affair in the late 19th century. “There’s still a ways to go,” Schama tells me, and as the 20th century approaches, “the death star, the dark planet of destruction exercises more of a gravitational pull.” But that will be for part three.

These volumes are an accompaniment to the 2013 landmark BBC television series of the same name, the opening episode of which brought Jewish history to 2.4 million people. It is through the 2014 PBS broadcast of The Story of the Jews that the British-born Schama was introduced to most American Jewish readers and viewers. Less known is that the series represents but the tip of the iceberg of his multitudinous career encompassing 17 books and more than 20 years of television—from 1995’s Landscape and Memory to 2015’s The Face of Britain, a history of Britain through portraiture.

Niall Ferguson, the British author of Civilization: The West and the Rest, calls Schama “one of the most brilliant historians [Britain] has ever produced,” labeling him “the Dickens of nonfiction.” Another Schama admirer is American writer and critic Leon Wieseltier, who first met Schama back in 1977 at Harvard. He tells me that Schama “knows how to tell a good story, but he actually, as a matter of methodological principle, believes in narrativity as the historian’s primary mode.” Schama has, he adds, “never met an uninteresting fact.”

The first time I meet Schama is in Amsterdam, where he is filming the Renaissance-themed episode of his latest tour de force: the BBC documentary series Civilizations. Premiering in Britain in late 2017, with Schama hosting six of the ten episodes, the show tells the story of art from the dawn of human history to the present day. The Rijksmuseum, the Dutch capital’s cultural treasure house, is closed for the day, and a gallery that would usually be teeming with tourists is deserted. The voices of the BBC film crew bounce off its dark blue-grey walls and vaulted ceilings.

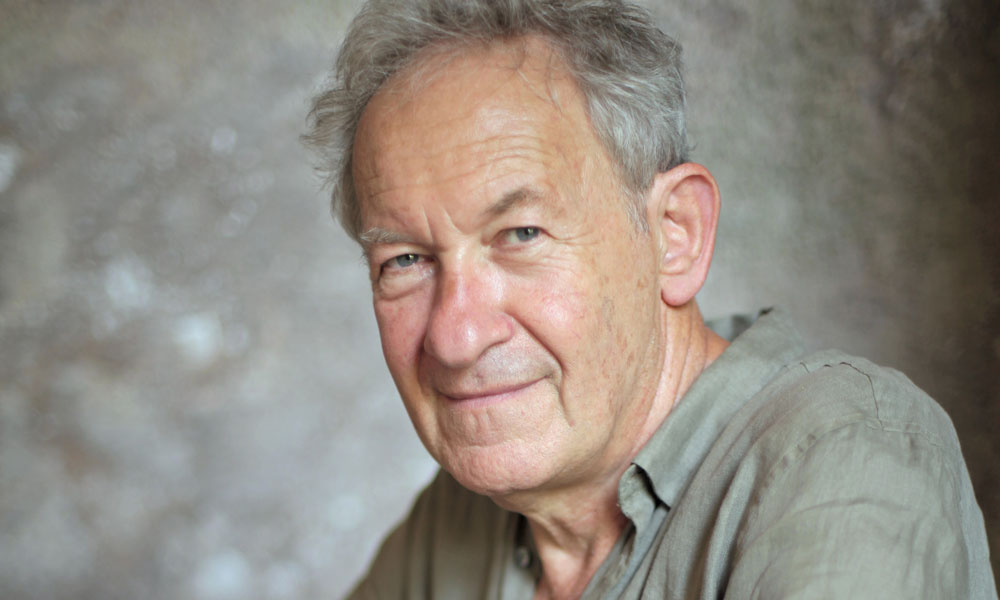

Seventy-two years of age and gray of hair, Schama wears a blue suit jacket atop an off-white shirt that hugs his middle. On set, he overflows with words, providing a running commentary on his every movement to the crew with no gesture unexplained. “I think I will be buried here, under the floorboards. Is that possible?” Schama quips to a museum staffer.

Schama has to deliver a stirring monologue on Rembrandt’s colossal masterwork, The Night Watch. He runs through some choice words: action, energy, vitality. “You name it, I’ll thesaurus it,” he jokes to his director. Between the history of Holland and the history of art, Schama is on his intellectual home turf—The Embarrassment of Riches, his 1987 study of Dutch culture, helped propel Schama to fame; the 2006 book and BBC documentary series, The Power of Art, solidified his reputation and art history bona fides.

Away from the camera between takes, he is just as voluble. His manner is akin to one long after-dinner speech—fluent, generous with jokes, anecdotes and observations that come from a place of deep knowledge and love of subject. Between scenes, the art on the walls of the Rijksmuseum arrests not so much his eyes as his entire body as he glides along the gallery, pausing to examine the landscapes and portraits. Schama is an intellectual raconteur, a bon vivant—a popular historian who moves between traditions and disciplines, all the while buttressed by a strong sense of Jewish identity.

As we settle in at a café in Little Venice, an oasis amid whitewashed villas, Schama orders a vitamin juice, fearing he’s fighting off a cold, along with a slice of passion fruit cheesecake. He sits across from me in a white linen shirt, and the joy he finds in narrative is evident as he recounts stories of his family. He’s demonstrative, even a little restless. While he talks, his hands always have to be doing something: topping up his water glass, jabbing at his cheesecake with his fork or toying with the sugar cubes and rearranging them into patterns.

To understand Schama, one must travel back to the banks of a river in Kovno Gubernia (in what is today Lithuania), amid primeval forests that once resounded with the cries of wolves and horses’ hooves. There stood the house of Schama’s mother’s grandfather, Eli. The timber trade was big business for Jews in the Baltic Pale, where Eli and his son Mark cut the timber down and floated it downriver on rafts. This part of the Russian Jewish world was not of the towns—Kovno, Vilna, Riga—but somehow not quite the shtetl either. It was a “physical and unlearned community but exuberantly earthy,” Schama tells me, “casually religious,” a breeding ground for the partisans of the future.

Mark—along with his three brothers—got out as the Cossacks closed in at the turn of the twentieth century, escaping to London’s East End and changing his employment from timber to butchery. Schama’s earliest memory of his grandfather—a habitual smoker of thick, yellow Russian cigarettes and consumer of vodka “at an incredible rate”—is of “being hoisted on his back and his singing Russian as well as Yiddish songs” and of having to be taken to the hospital to have his stomach pumped when a young Schama was left alone in the presence of eight small shot glasses of vodka. “My mother said, ‘What will happen to him?’ and the doctor said, ‘He’ll have a hell of a hangover.’” It was in the East End, home to a whole generation of Jews who escaped the Russian Empire in the nick of time, where his mother, Gertie, was born.

Schama’s father, Arthur—a schmatter by trade—was also born in the East End, the fifth child and third son of a “scholar-cum-rav-cum-businessman” in a generation of 13 children. Schama never knew his father’s father, whose origins can be traced back to Botosani, today in the Moldavian region of Romania, though ancestrally this side of the family was said to have come from Izmir, Turkey. This side of the family was Sephardi, but in Romania, says Schama, “the family half-Ashkenazified itself,” resulting in “complicated family debates and discussions about whether you should cook the charoset or not.”

“I had a very happy, eccentric, small childhood,” Schama says. His parents’ marriage was colored by Arthur’s patchy business career. The good times meant a home in the posh part of Southend, east of London, with walks on the beach and trips to the amusement park. Other times were more precarious because of Arthur’s tendency to overinvest in spectacularly colorful fabrics. “We’d sell the flat and the house and the car, and my mother would go crazy,” Schama reflects. A working woman during the Second World War, afterwards Gertie “was a Jewish housewife and really hated it,” which “slightly embittered their relationship. It was okay so long as things were going well for my father. When they weren’t, my mother could get really nasty.” If Arthur had a bad week, he’d come home for Shabbat dinner slightly tipsy, unable to face Gertie sober.

I wanted to do everything except Jewish history. I thought it may work for some people, but it isn’t working for me, as a historian, to deal with a culture that is my own.

Her husband’s ups and downs, however, gave Gertie a second life. Back out in the workplace, she ran a Meals on Wheels operation for housebound Jews in the East End and later founded and fundraised for a day center for the Jewish elderly. A brutally funny and outrageous woman, her late-in-life career liberated not only her but her husband, too. “My father actually basked in her reflected glory,” Schama remembers. “He no longer bore the burden of being the major breadwinner. He felt that his wife’s obvious potential that had flowered during the war was finally allowed and she was amazingly happy and gregarious.”

The problem was that Arthur had been forced into a trade he hadn’t wanted to be in in the first place. “My father’s passion was always to go into the theater, and the story was that his father said to him, ‘You’ve got to go into a proper business, and if you go into the theater, don’t bother coming home again.’” A tremendous speechmaker with a thespian spirit, Arthur read Balzac and Dickens and “was like a lot of his generation a street corner orator against Mosleyite blackshirts,” the British Union of Fascists, in the East End of London, which during the 1930s was a center of both fascist and anti-fascist activity.

Schama imbibed from his father his sense of drama and theatricality. Arthur took his son to the theater, taught him poetry and great reams of Shakespeare and was his main coach in public debate. “He said that a Jew’s best weapon is always his mouth,” says Schama. The other important gift his father bequeathed to him was the freedom to follow his passion—which he had not been given. Although Gertie might have wished for her son to become something “Jewishly sensible” like a lawyer, “my father said you should do exactly what your heart points you to, which was being a writer and a teacher. He gave me that.”

The Judaism of Schama’s childhood was in keeping with the prevailing British Orthodoxy of the period. It meant going to shul every Shabbat, not driving or using public transportation that day, cheder three times a week and keeping kosher. But it also meant turning a blind eye in a fish restaurant when they went out to eat and carrying what you felt like carrying on Shabbat for good measure. “The Talmud is full of these arbitrary conventions. As I can hear my father say, ‘Mishnah schmishnah!’”

It also meant Saturday nights spent at the Golders Green Youth Club, “a bizarrely racy place” full of menacing Jewish rebels in Edwardian-era rags armed with razor-blade knives. “There was often blood on the floor of the Joseph Freedman Hall,” Schama recalls. “Charles Saatchi”—the advertising guru and art collector—“and I spent an evening many years ago reminiscing about an absolutely infamously violent woman called Kitty Bennett. I said to Charles, ‘Did Kitty Bennett force you to dance with her?’ She smelt horrible—I still remember that. She was gigantic and ugly—she was sort of like a bus, and red-faced and this horrible bleached hair. I said, ‘I had to dance with her,’ and he said, ‘You are lucky, I had to snog her!’” (Saatchi was unavailable for comment.)

In his adolescence, Schama says he developed “pretentious political principles” and became part of Habonim, the socialist Zionist youth movement. “Habonim was fantastic, partly because those girls wore no makeup and were very sexy and were full of high-flown principles and you went on marches. There I was, puppily in love with the blonde Jennifer Jacobs, marching and singing the Internationale, and it was heaven.” In the spring of 1963, Schama did a stint on Kibbutz Beit HaEmek in Israel’s western Galilee. “I remember not liking the collectivism very much. I loved the work, weirdly enough—some of it. The grape vineyards were wonderful, and the chicken house was horrifying.”

After the kibbutz came college, reading history at Christ’s College, Cambridge, where Schama embarked on his career in academia. “When I came up to Cambridge, he was already a legend,” says Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, who started his undergraduate studies a few years after Schama. In Cambridge, there is a small independent Orthodox synagogue, and Sacks noticed Schama’s presence there in the weeks leading up to the Six-Day War. “Simon could not be called a regular—I had never seen him there, but such was the anxiety we all felt in those three weeks before the war that Simon turned up to pray, and that made a huge impact on us.” He continues: “It’s like when I was Chief Rabbi. When the Chief Rabbi visits you in hospital, you know you must be ill. So when Simon comes to pray, someone must be in trouble.”

At Cambridge, Schama ran an informal Jewish history seminar with Nicholas de Lange, who would later become Amos Oz’s longtime translator. This attracted the attention of Lord Victor Rothschild, who was looking for someone to complete a history of the great Zionist philanthropists Baron Edmond and James de Rothschild and the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association, for James’s widow, Dorothy. The book, Two Rothschilds in the Land of Israel, published in 1978, was Schama’s first work of Jewish history.

Unbeknownst to Schama when he took the job, Victor had promised Dorothy “a delivery date that was impossible,” and so Schama was required to hurry “through the narrative, particularly the second half of the book, much more expeditiously and opportunistically than I really should have,” he says. Some of his conclusions, which today seem perfectly innocent—that the Rothschilds’ success in colonizing parts of Palestine depended on written-off capital investment and Arab labor—was “sufficiently off track from the pure Zionist line for uncles and aunts not to talk to me ever again, so I thought, I don’t need this.”

After Two Rothschilds, Schama decided to eschew writing about Jewish history. “I specifically had a period where I wanted to do everything except Jewish history. I thought it may work for some people, but it isn’t working for me, as a historian, to deal with a culture that is my own,” he reflects, “and I thought, I just need to steer clear of this subject.” Schama did not return to Jewish history for another 30 years.

The dedication of Schama’s daughter Chloë’s first book, the historical novel Wild Romance, reads, “For my father, who taught me how to tell a story.” In a conversation at London’s Jewish Book Week in 2015, Chloë, currently a senior editor at Vogue in New York City, described how he would read Charles Dickens and Roald Dahl to her before bed and tell made-up “Masha and Sasha” stories on the drive to school.

Whether as a historian or art critic, profiler, food writer or political commentator, the raison d’être of Schama’s life has been to tell stories. It is hard to imagine Schama as anything but a popular historian. “It’s not for me,” Schama says of the cloistered academic life. But of course, those who choose the path of popular history run the risk of being taken to task for it, on account of the seemingly never-ending tension between academic and popular history.

Schama encountered this almost immediately with his gallivanting 1989 chronicle of the French Revolution, Citizens. Published to coincide with the bicentennial, the book emphasized terror and violence as inherent to and the driver of the French Revolution. The late venerable Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm argued Schama was too negative, neglecting those French men and women who participated happily and idealistically in the revolution. Alan Spitzer, a specialist in French intellectual history at the University of Iowa, accused Schama of “tendentious manipulation of sources and the facile disposal of alternate interpretations that demand consequential refutation.” The late historian of the French Revolution Norman Hampson also had sharp words, writing Schama had “read very selectively” and quipped, “Schama’s argument is always intelligent and often persuasive, but his facts are not always reliable.”

“I didn’t really care about what was said in the press and in the reviews, but there were some people who stopped talking to me” after Citizens, Schama says. That sort of thing bothered him at the time, but he now reflects, “If you do the kind of history I do, you have to be prepared to take those knocks, actually. I mean you’re talking to me now at a very grand old age, so it doesn’t bother me at all.”

Lynn Hunt, a professor of French revolutionary history at UCLA who has known Schama since the late 1970s, explains that to specialists, Citizens was not particularly convincing because of its overwhelming emphasis on violence as the revolution’s major characteristic. “The book was very successful because it was incredibly well written, a gripping narrative with a real sense of drama,” Hunt tells me. “I certainly shared the general consensus that the book didn’t offer a particularly interesting thesis.” Still, Hunt believes Schama “is an incredible example to the rest of us for how to interest the general public.”

History going back to Thucydides and Tacitus began as an act of honor, being a pain in the side of tyrants. It wasn’t a kind of academic pursuit—it was a kind of citizenship pursuit.

Ferguson, another British televisual historian, first met Schama in 2002, when he was working on his own book and historical documentary series, Empire. He says Citizens is an example of Schama’s “extraordinary virtuosity” as a writer, arguing that even if one wishes to challenge its thrust, it must be considered his best book. “I’m somebody who’s written for a popular audience. There are some academic types who can’t do that,” he says. “There’s a mind-set of bitterness and jealousy. They nitpick and conveniently overlook the most scholarly work that we’ve done, as if Simon had never written The Embarrassment of Riches, only A History of Britain.”

With A History of Britain, Schama became Britain’s national biographer, producing at the turn of the millennium a history that sprawled over three hardback volumes and 15 television episodes. It was the series that elevated him to first among Britain’s televisual historians. Such is his standing that when in 2010, the Conservative-led government decided to rewrite the national history curriculum, they turned to Schama. Michael Gove, then-education secretary, praises Schama’s “clarity of thought, rigorous analysis and ability to craft a compelling narrative” as “second to none.”

Midway through the process, however, Schama had a very public falling out with Gove, calling one particular version of the new curriculum “insulting and offensive…pedantic and utopian” at the Hay Festival in April 2013, although he laughs about it now. “He’s not a crude or unsubtle person,” Schama says of Gove, “but he produced this first draft of core people who should be part of any British history curriculum which was ludicrous, so that’s when I really had a go at him, but he took it on board” and approved of its final iteration. “There is no doubt that the new curriculum is far superior to its predecessor and that is thanks in no small part to Simon’s candid advice,” Gove says tactfully.

“This is a Jew,” the voice-over intones, as a sequence of smiling faces passes before us: secular and religious; black and white; dark hair and light. “And so is this. This is a Jew,” it continues, “and this, and this.” Then cut to Schama, standing by a bus station on a busy street in Tel Aviv. “And so am I.”

Thus began The Story of the Jews. Broadcast in 2013 over five hours on the BBC, it was as if, having spent years on television darting between continents and wandering the art galleries of Europe, he was reintroducing himself to the British public as a Jew. The personal aspect to this project is one of the reasons it is so riveting. There is also a wonderful sense of symmetry or wholeness about these scenes, for in their nod to Jewish plurality, they mirror the opening words of Schama’s troublesome first work of Jewish history, Two Rothschilds: “Historically, there is no such thing as a ‘typical Jew.’” Not merely a coming out, it was also a return.

It was Adam Kemp, then the BBC’s commissioning editor for arts, music and religion, who in 2009 approached Schama with the idea to tell Jewish history to a prime-time audience. “He phoned me up and said, ‘It’s obvious what you should do next and you’ll either love it or you’ll run a million miles away from it. Let’s have a drink tomorrow and I’ll tell you what it is.’” Almost instantly, Schama knew exactly what Kemp had in mind—the very thing he’d been instinctively “running away from” since Two Rothschilds. At the same time, however, he realized “if the BBC wants to do it, I’m very much up for it. I thought it was an incredible opportunity.”

The series had a cultural significance beyond its impact as a work of history. Schama tells me that he could see the climate for Jews was “getting darker and more turbid” in Britain, and indeed, it was reassuring for British Jews and illuminating for the wider public to have this great human story, this singular Jewish history, portrayed on national television. Sacks says, “It was a very important statement by Simon about his own identity as a Jew and as a supporter—admittedly a critical supporter—of the State of Israel. It took some courage to do that on British television.”

Schama was more emotionally invested in this series than any other, he tells me. “There were moments when I just pretty much lost it,” be it in destroyed graveyards in Alexandria, decayed wooden synagogues in Lithuania, or on the roads outside Seville and Cordoba. But The Story of the Jews was “written in the spirit of defiant vitality,” Schama insists. The Holocaust is very much present, but it is not a history of the Holocaust. “I really didn’t want to do that,” Schama says of shots of the ghetto in flames and bulldozers piling up bodies, though “not because I’m in denial at all.”

The Story of the Jews was not without its controversies, but perhaps its most discussed moment came in its third episode, which traced the great arc of the Jewish Enlightenment from the excommunication of Spinoza through to the Holocaust. The specter of anti-Semitism looms large as Schama, sitting in Vienna’s historic Café Sperl, gives an accounting of Theodor Herzl’s turn toward Zionism.

“I’m a Zionist,” Schama says to the camera. “I’m quite unapologetic about that, because it comes down to this: Was Herzl, who had a sense of a catastrophic event just around the corner, telling the truth or wasn’t he about whether it was possible still to live the Enlightenment dream here in the German world? Of course, he was. With that knowledge, with that sense of the Jews never having had the power of their own national home,” Schama concludes, “how could you not be a Zionist?”

Schama saw this declaration as necessary. “I was and still am so outraged by the equation of the word [Zionism] with a kind of egregious colonialist racism. I was determined to take it back, and I knew it would have an effect,” Schama says. “I thought about doing it and was determined to do it.” In spite of the reaction—the Palestine Solidarity Campaign complained the BBC went too far in “giving a platform to an openly pro-Israeli commentator to make the ‘moral case’ for Israel—he remains “completely unrepentant and clear-headed” about it. As Sacks reminds me, Schama’s stance makes a difference. “You have many universities today in Britain and elsewhere where it has become very difficult to say these things, so the fact that the BBC is willing to give space for those things to be said is terribly important.”

Our final conversation comes after the inauguration of Donald Trump, and having just finished his second volume of The Story of the Jews, Schama is in a contemplative, retrospective mood “What we’re witnessing is a return to tribalism,” he says with a certain clarity. “For a long time, we pretended that this kind of hatred and electrification of anger was an extension of something else—class problems, the economy, and so on—but none of that is ultimately true. It has its own ferocious psychological engine and that’s what we’re facing now.”

Online and on television, Schama has been animated and upfront about his fears regarding where all this is going, declaring Trump to be “incredibly scary and authoritarian” and “beyond absurd” on British television back in January and warning that anti-Semitism has long been part of political populism. “I’ve been working on the mysteries of nationhood all my life,” he says, pointing to a professional but also personal drive behind his outspokenness. “When there’s this violently hostile wave of anger against immigrants, I think if you’re a historian and you nourish your Jewish identity, I was bound to feel and to want to argue seriously.”

Schama’s outspoken commentary, not only on Trump but on Brexit too, is in keeping with how he has lived his life as a most public historian. For Schama, history is a civic duty that thrives as a form of engagement, active—perhaps even activist—and connected with the contemporary world. History going back to Thucydides and Tacitus, Schama passionately informs me, “began as an act of honor, being a pain in the side of tyrants. It wasn’t a kind of academic pursuit—it was a kind of citizenship pursuit.”

Schama recounts the story of Marc Bloch, the French medievalist who cofounded the Annales School of social history in 1929. During the Second World War, initially exempted from the Vichy government’s anti-Semitic program, Bloch relinquished his official role in the Annales School’s publication under pressure. Bloch later joined the Resistance but in March 1944 was captured, tortured by the Gestapo and killed. Schama pauses for a moment before telling me, “There’s a relationship for me between a deep originality and profundity” of his work and the “extraordinary moral decency and nobility” of his public life.

Bloch’s fate is one Schama finds deeply moving and genuinely tragic. More than that, Bloch serves as an exemplar or paradigm for what the historian should aspire to be. “In times like these, to just go about your business as a historian and not pay attention to the current atmosphere, then history is just a hobby,” Schama says forcefully. “It’s kind of a stroll down memory lane—and I’m too old to really want to do that.”